My guest today is my good friend Mark Richards. Mark is an independent hands-on software architect, with 20 of his 30 years of experience in the industry playing some type of architecture role on a myriad of different software projects. He is the author of several books including Java Message Service, 2nd Edition, and is featured in the book 97 Things Every Software Architect Should Know. In addition to that, he is a frequent speaker on the conference circuit (which is how we met) and gives various extremely popular software architecture trainings around the world.

In this episode we discuss his keynote from the O'Reilly Software Architecture Conference in London, which took place in October 2016.

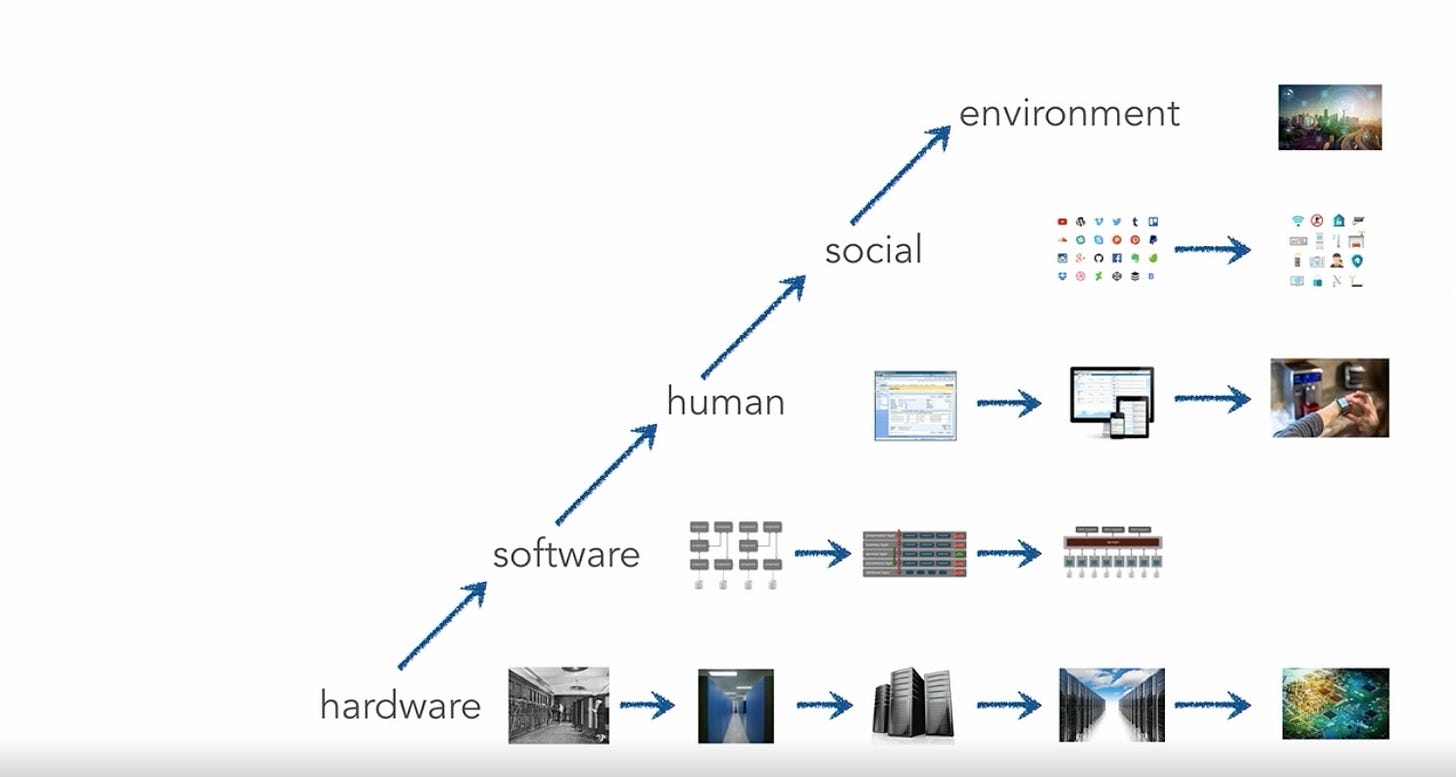

After Mark provides us with some interesting aspects of his background (he started his career as an astronomer!), we start by discussing the horizontal and vertical aspects of the evolution of software architecture, and how each move along one axis can drive changes in the opposite axis, as depicted in Mark’s keynote slide:

Some of these drivers are technical - especially often hardware taking some time to catch up with the needs of newer ideas and software - but other times these changes are driven by changes in the business. Mark relates a story that I tell in my book, Migrating to Cloud-Native Application Architectures, about the transitions that have taken place in the last twenty years in how we perform the simple task of checking our bank account balance. These transitions have caused banking systems to transition from what Mark calls controlled access, such as visiting a human teller in a bank branch, to uncontrolled access, such as using a mobile banking application. These changes in access have caused a radical increase in the scale demands place on these same systems. Most legacy systems were never built to handle this kind of demand, and this has driven us toward new types of architectures that scale much better.

The conversation then transitions into coverage of three specific factors that drive architectural decision making;

agility: having the characteristics of speed and coordination; the ability to react quickly and appropriately to change.

velocity: the speed of something in a given direction.

modularity: having independent parts that can be connected or combined in different ways.

Mark describes these factors as “ingredients that go into an evolutionary cauldron.” Many companies are trying to embrace agility, both from a technology and a business point of view. And this “agility in isolation” is what causes many businesses to fail, as they spin rapidly in circles and never go in the right direction. This is where the importance of velocity comes into play. Agility combined with velocity allows us to move quickly, respond to change, and move in the right direction. But these must also be combined with modularity, which itself has both a technical and a business aspect.

As we discuss business modularity, it becomes time for the requisite Conway’s Law reference. But we quickly transition back to technical modularity, and the concepts of loose coupling and high cohesion. We’ve talked about these things for many years, but it very often doesn’t lead to significant improvements in actual project architectures. Why? Mark sees the problem is very often inherent in a lack of drivers. Modularity comes with a definite price. It is very often driven by the desire for agility - it’s hard to achieve agility with a monolith. But the more modular our architecture becomes, the less reliable and available it becomes as we introduce distribution. Coming back to the idea of drivers, Mark brings up Martin Fowler’s blog entitled “Sacrifical Architecture,” or this concept of throwing away portions of our architecture that no longer support the required business functionality, something that we can only accomplish with a truly modular architecture. We see these same drivers inherent in the move to microservices, which result in the same costs.

Volatility often becomes one of the key drivers moving us toward modularity and microservices. Many of the aspects of our system - such as admin or reporting functionality - simply aren’t that volatile. And so we can make the mistake of moving these things to microservices when there isn’t any payoff. But it always comes with a cost (what I like to call “the distributed systems tax”).

And so we turn the discussion to the million dollar question: “What microservices should I have?” Where should I draw the boundaries? I relate the analogy of how we described velocity in physics as a vector, where the magnitude of the velocity was indicated by the length of the vector, and the direction of the velocity was indicated by the direction of the arrow. I compare these to the discussion of independent value streams that we find in the DevOps conversation. How many velocity vectors should you have? Well, how many different value streams do you have that move in different directions and at different speeds? These different velocity vectors can then be aligned with different deployable artifacts with independent lifecycles (i.e. microservices), thus preventing the tangling of these vectors together. Mark sees this as the perfect blending of agility, velocity, and modularity.

Mark transitions the conversation back to the three ingredients and how they provide us with a high degree of deployability, testability, and scalability. These lead us toward a definition of competitive advantage. But it’s about more than being able to push out product quickly. It’s also about having a feedback loop to which we can react quickly and change appropriately.

We start to wind down the conversation by discussing “What’s Next?” As Mark described three ingredients in the evolutionary cauldron, he also described three characteristics of the next evolutionary stage in software architectures:

A tighter integration of data and functionality

Self-healing systems

Architectures that constantly evolve

Streaming architectures are one step in the direction of a tighter integration of data and functionality, but Mark sees a greater paradigm shift in not seeing data as somehow a separate entity in the architecture, but part of the greater whole.

Reactive architectures are currently one of Mark’s key passions. Mark describes the application of patterns that allow systems to grow without any human intervention. Systems that can handle any spikes in load or transaction volume. Systems that can self heal, almost like biological systems. Patterns that include the Thread Delegate pattern and Workflow Event pattern.

The final item is really a call to action, to discontinue the fool’s errand of gazing into crystal balls, trying to figure out what our architectures will look like. It’s impossible to do that kind of predictive analysis anymore. But instead we leverage these first two aspects to create architectures which truly can evolve over time.

Mark closes with an exhortation to aspiring software architects to focus on improving their people skills. He sees this as not only the most important skill set for the software architect, but also the most difficult one to learn.

Links:

Martin Fowler’s Sacrificial Architecture

Eric Evans’ Domain Driven Design

Find Mark’s Software and Enterprise Architecture training courses offered through No Fluff Just Stuff

Share this post